Top Ten Famous Bermuda Triangle Disappearances-Debunked!

(Originally published on WordPress on February 17th, 2022)

It was probably inevitable that my tour of the world's infamous paranormal "triangle" hotspots would bring me back to the one that started them all.

The idea that the Bermuda Triangle is an inherently more dangerous and mysterious part of the seven seas seems to have started after the Flight 19 incident in 1945, especially after this article that appeared in the September 17th, 1950 edition of the Miami Herald. The term "Bermuda Triangle" was coined in February of 1964 by Vincent Gaddis in an article he wrote for the pulp magazine Argosy. But it wasn't until Charles Berlitz wrote the book The Bermuda Triangle in 1974 that the public learned just how deadly this stretch of the Atlantic was.

Or maybe not, as librarian Larry Kusche demonstrated in his book The Bermuda Triangle Mystery-Solved, published the following year. He found that Berlitz and several other authors had either exaggerated or omitted details, making some incidents sound more mysterious than they actually were, or even invented some incidents out of whole cloth (like a plane that allegedly crashed off Daytona Beach in 1937 that Kusche could find no newspaper records of).

One particularly egregious error that Kusche found was Berlitz writing about an ore carrier that allegedly vanished three days from an Atlantic port. Kusche found the ship had actually departed from a port of the same name on the Pacific coast! Kusche deadpanned that Berlitz's research was so sloppy that "if Berlitz were to report that a boat was red, the chance of it being some other color is almost a certainty."

Indeed, the findings of the Coast Guard, Lloyd's of London, and NOAA seem to back up Kusche's conclusions that the so-called Bermuda Triangle is no more dangerous than any other part of the ocean. So what is the truth behind some of the more infamous vanishings? Let us examine ten such incidents to determine the real stories behind them, starting with:

1. The Ellen Austin (1881)

This particular derelict ship story begins on the outskirts of the Sargasso Sea when the crew of the 1800-ton schooner comes across an unknown and abandoned vessel on a voyage from London to New York. Part of the Ellen Austin crew boards the ship and confirms that not only are there no souls aboard, but they cannot find any sign as to why the crew may have abandoned ship. Everything, including the mystery ship's cargo of mahogany, is in order, except for the captain's log and the ship's nameplate, which are missing.

The captain of the Ellen Austin orders the salvage crew to steer the mystery ship to New York. Two days later, the ships are separated in a storm, and when the Ellen Austin finally catches up with the other ship, the salvage crew has also gone missing.

The tale appears to have entered the popular imagination after it was retold by Rupert Gould, a retired Royal Navy commander, in his 1944 book The Stargazing Talks. There are several variations of the story. One tells of the Ellen Austin captain trying to send a second salvage crew over, only to abandon the mystery ship when the terrified crew refuses to board it. Another tells that the Ellen Austin never saw the mystery ship again after being separated by the storm. But which is the correct version of the tale?

If Larry Kusche is correct, none of them are because he could not find concrete evidence that the incident ever happened. A schooner named Ellen Austin was operating in the North Atlantic at the time (built in 1854), although it was called Meta until 1880. Kusche could not find any casualty reports from around the time that suggested anything unusual happening to the ship's crew between leaving London on December 5th, 1880, and arriving at New York City on February 11th, 1881. Furthermore, the ship stopped in St. John's, Newfoundland, which would have taken her far away from the Sargasso Sea.

Of course, Kusche's search for the truth was complicated by the fact that Gould never gave a source for where he originally heard the story. However, an investigation by the website Sometimes Interesting found that the earliest mention of the incident came from a 1906 newspaper article from the Daily Deadwood Pioneer Times, which gave the year of the incident as 1891. That webpage offers a detailed history of the Ellen Austin that I highly recommend you read for yourself (including an 1857 incident where the captain beat a crew member with wire rope and set his dogs on him).

Ultimately, neither they nor Kusche could find any concrete evidence that the Ellen Austin encounter really did happen. It could simply be a mixup of the records that prevents us from getting the real story, but until we get better confirmation, perhaps it's best to regard this as a nautical tall tale.

2. USS Cyclops (March 1918)

This nearly 20,000-ton US Navy collier sailed into history after departing from Barbados on March 4th, 1918, en route to Baltimore, Maryland, with 306 crew and passengers on board. When the ship failed to arrive on schedule on March 13th, a massive search was launched, which could not find any wreckage.

Some more fantastically minded Triangle enthusiasts might point to UFOs or Atlantis or the Kraken or interdimensional portals to explain the vessel's disappearance, but there are plenty of more logical explanations:

-The ship's captain, George W. Worley, had a bad reputation. He was a violent drunkard who verbally abused crew members over minor infractions and even once chased the ensign with a loaded pistol. He was also reviled for his pro-German sympathies, and subsequent investigations even found that he was born in Germany. This has led some to speculate that Worley may have spirited the Cyclops away to Germany to help with their war effort. It certainly doesn't help that one of the ship's passengers, Alfred Louis Moreau Gottschalk (consul-general in Rio De Janeiro), also held pro-German sympathies. However, there are no records that the ship ever came near Germany, and there is no concrete evidence that the vessel may have run across a U-boat or mine during its voyage.

-The crew of the molasses tanker Amolco claimed to have spotted the Cyclops near Virginia on March 9th, the day before a massive storm swept the area, which could have sunk the vessel. However, this makes no sense, as that means the Cylcops would have safely reached port the next day, three days ahead of schedule. This isn't to say the ship couldn't have conceivably encountered a storm en route to Baltimore, but the March 10th storm almost certainly wasn't it.

-The most likely theory is that the highly corrosive manganese ore that the Cyclops was carrying may have corroded the I-beams running along the ship's length, eventually causing it to break in half in the middle of the ocean. BBC journalist Tom Mangold also proposed in a 2009 documentary that the ore could have become wet due to the cargo hatch covers being canvas, which could have caused the cargo to shift and cause the ship to list, leading to its foundering in bad weather.

The Cyclops' sister ships, the Proteus and the Nereus, would also vanish while traveling the same route in November and December of 1941, respectively. The last, the Jupiter, later became the USS Langley, the US Navy's first aircraft carrier, which was scuttled off the southern coast of Java on February 27th, 1942, after sustaining heavy damage from Japanese bombers.

3. SS Cotopaxi (December 1, 1925)

You may remember this ship for its appearance in Stephen Spielberg's classic 1977 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind, where the long-lost bulk carrier is found sitting intact and abandoned in the middle of the Gobi Desert. The ship's mysterious vanishing after departing from Charleston, South Carolina, on November 29th, 1925, with a cargo of coal bound for Havana, led many to connect the ship's disappearance and her 32 crew members with the Bermuda Triangle.

However, we know this isn't true for two reasons. The first is that the Cotopaxi sent a distress signal on December 1st, reporting that the ship was caught in a tropical storm and was listing and taking on water. Many experts suspect the ship's wooden cargo hatches may have been damaged, thus allowing water to flood. Several family members of the Cotopaxi's crew even sued the ship's owners when a carpenter revealed that the company had ordered the ship to depart for Havana before he could finish repairing the dilapidated hatch covers.

The second reason is that the ship's wreck has since been found. No, I'm not talking about that news story from 2015 about the Cuban Coast Guard finding the ship abandoned floating somewhere west of Havana. That was from a satirical newspaper called the World News Daily Report and has been debunked by Snopes.

The actual wreck of the Cotopaxi was found forty miles east of St. Augustine, Florida, sometime in the 1980s. However, it wasn't positively identified as the Cotopaxi until January 2020, after about fifteen years of work by marine biologist Michael Barnette. The ship's wreck was later the subject of the series premiere of Shipwreck Secrets on the Science Channel the following month.

4. Flight 19 (December 5, 1945)

By far the most infamous Triangle vanishing was the day five Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers flew off into history, taking their 14 crew members with them and helping to cement the Bermuda Triangle's place in the popular imagination. But was the squadron vanishing really as mysterious as its reputation claims it is? Let us examine the timeline of events on that day and find out.

The squadron took off from the Naval Air Station in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, at 2:10 p.m. with Lieutenant Charles C. Taylor in command. The squadron was set to perform an exercise called "Navigation Problem No. 1," which involved a practice bombing run on the Hens and Chickens Shoals in the Bahamas. They were the 19th squadron scheduled to complete the three-hour run that day.

The squadron completed the bombing run around 3:00. It continued flying due east for another 77 miles as instructed, intending to turn north over Grand Bahama Island and then return west for home. However, this is when the trouble started, as Taylor suddenly sent a distress signal around 3:30, stating, "I don't know where we are. We must have gotten lost at the last turn."

This transmission was overheard by Lieutenant Robert Cox, who was preparing to leave Fort Lauderdale with his own squadron of bombers. When Cox asked Taylor to clarify what was going on, he got this baffling answer:

Both of my compasses are out and I am trying to find Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I am over land but it's broken. I am sure I'm in the Keys, but I don't know how far down, and I don't know how to get to Fort Lauderdale.

-Lieutenant Charles C. Taylor, December 5th, 1945

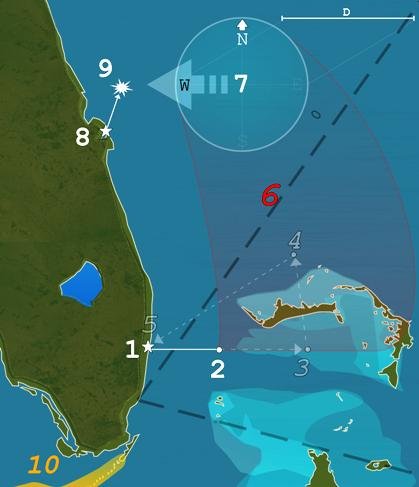

Even if we acknowledge that Taylor was almost certainly mistaking the northern half of Abaco Island for the Florida Keys, it is still a baffling error. How did Taylor think the planes could have gone that far off course? Here's a map of the region to show you what I mean.

0. The outline of the Bermuda Triangle 1. Fort Lauderdale 2. The Hens and Chickens Shoals 3. The position where Flight 19 was supposed to turn north 4. The position where the Flight was supposed to turn back to base 5. Fort Lauderdale again 6. The red-shaded area shows where the planes could have been 7. The area of the planes' last known position 8. Banana River Navy Air Station, from which the PBM Mariner took off 9. Last known position of the Mariner 10. The Florida Keys, where Taylor thought he was

True, Flight 19 was experiencing compass problems, but it's hard to believe that that could have brought the plane that far off course. In any case, Taylor decided that flying northeast would get them back over land, which should have taken only twenty minutes.

Lt. Cox offered to come and find Flight 19, but Taylor turned him down, sure he knew where he was. When that didn't work, one of Taylor's students suggested flying west, arguing that any Fort Lauderdale plane worth its salt would follow the setting sun. Even as late as 5:00, Taylor was still convinced beyond all reason that he was over the Gulf of Mexico and could be heard saying, "Change course to 90 degrees [due east relative to Fort Lauderdale] for 10 minutes." To which a frustrated trainee responded: "Damn it, if we could just fly west, we would get home! Head west, damn it!" By this time, the Flight had drifted into an oncoming storm.

Around 5:50, several radio stations had managed to triangulate Flight 19's position as being within 100 nautical miles of 29 degrees north, 79 degrees west, which enabled the Navy to start planning a rescue mission. This was hampered somewhat by Taylor's refusal to switch to his radio's search and rescue frequency.

By 5:24, Taylor seemed to have finally realized his error and ordered the planes to head west, only to change his mind around 6:04 and tell his trainees, "We didn't fly far enough east. We may as well turn around and fly east again." The last message ever received from Flight 19 came at around 6:20:

All planes close up tight... We'll have to ditch unless landfall...When the first plane drops below ten gallons, we all go down together.

-Charles Taylor, December 5th, 1945

The plot thickened further after 7:00 when three flying boat aircraft set out to search for the missing bombers. One of them, a Martin PBM Mariner, which had taken off from the Banana River Navy Air Station with 13 crew members at 7:27, vanished after sending a routine radio call three minutes afterward.

With the complete timeline laid out, it's self-evident what really happened to Flight 19; they got lost and eventually ran out of fuel. Indeed, while an experienced pilot, Charles Taylor was not exactly competent. He had gotten lost twice while fighting in the Pacific theatre of World War II and had to ditch his planes both times. Even on the day of Flight 19's mission, he arrived 25 minutes late and asked someone to take his place. His reasons are unknown (I've read some sources suggesting he had a hangover, but I haven't confirmed it.) If that wasn't bad enough, Taylor didn't even bring essential navigational equipment like a watch or a plotting board. Indeed, the only reason the Navy didn't ultimately pin all the blame on Taylor was because his mother begged them not to ruin her son's reputation.

As for the PBM Mariner, that plane had an unfortunate history of gas leaking out from fully loaded fuel tanks, often setting off catastrophic explosions. Indeed, the crew of the tanker SS Gaines Mills witnessed a mid-air explosion at around 9:12 a few miles off Cape Canaveral and later found an oil slick in the water around where the blast took place. The escort carrier USS Solomon had been tracking the Mariner on radar and had lost the flying boat in that exact position.

5. Star Tiger and Star Ariel (January 30, 1948; January 17, 1949)

Both of these incidents involved Avro Tudor Mark IVB passenger planes belonging to British South American Airways, and both vanished while covering roughly the same route.

The Star Tiger set out from Lisbon, Portugal, on January 28 and stopped in Saint Maria in the Azores to refuel. However, the airliner departed sooner than expected as pilot Brian W. MacMillan wanted to get ahead of a storm set to drift across their route. The plane took off at 3:34 p.m. with 25 passengers and crew (including distinguished World War II veteran Sir Arthur Coningham) on the 29th.

The Star Tiger flew at a shallow 2,000-foot altitude to avoid the worst headwind. At 3:15 a.m. the following day, the plane radioed its position to its destination in Bermuda and estimated its arrival time as 5 a.m. It was the last that was ever heard from the Star Tiger. After attempting to contact the aircraft three more times and receiving no response by 4:40, the radio operator in Bermuda declared a state of emergency. The rough weather hampered the search, and it was called off after only five days.

While subsequent investigations of the Star Tiger's loss have been unable to determine the exact cause of the plane's loss (especially with the absence of any wreckage), they have determined that the aircraft had more than enough fuel to reach Bermuda. They have also ruled out engine or structural failure, as the plane was designed to run on as little as two engines, and the craft was flying at a low enough altitude that cabin pressure shouldn't have been a problem.

The most likely possibility was that, given that the crew kept reporting that they were flying at 20,000 feet instead of 2,000 feet, they may have forgotten their actual altitude and accidentally flown the plane straight into the ocean, likely due to fatigue after a long flight.

The Star Ariel departed from Kindley Field in Bermuda at 8:41 a.m. on January 17 of the following year, with 20 passengers and crew en route to Kingston, Jamaica. Unlike the Star Tiger, the Star Ariel flew in excellent weather. The plane sent two radio messages at 9:32 and 9:42, reporting that it was flying 150 miles south of Kindley Field at 18,000 feet and would reach Kingston at 2:10. It was never heard from again. Despite a six-day search covering a million square miles, no trace of the plane was found.

Subsequent investigations found that the Star Ariel had switched to Kingston's frequency at 9:37, which was unusual given that the plane was still close to Bermuda. This may have been combined with problems with radio communication, including ten-minute blackouts, which may have led Kingston radio to miss any distress calls the plane may have made.

Again, guesses as to what may have brought the Star Ariel down are scarce, given that no wreckage was found. In the same 2009 documentary mentioned in the Cyclops entry, Tom Mangold suggested that faulty heaters may have brought down both planes. The Star Tiger flew at such a low altitude because its heater was broken, thus leaving it little room to maneuver in emergencies. Meanwhile, the Star Ariel could have suffered from a mid-air explosion due to hydraulic vapors being exposed to the heater.

In any case, the Tudor Avro was retired from passenger service and switched to freighter service instead. A subsequent attempt to return two Avros to passenger service ended when the Star Girl was involved in the Llandow air disaster of March 12, 1950, when the plane stalled due to overloading upon approach to RAF Llandow in southern Wales. Of the 83 passengers and crew on board, only three survived, making it the deadliest air disaster in history at the time.

6. Douglas DC-3 NC16002 (December 28, 1948)

The Douglas DC-3 has long had a reputation as one of the most reliable aircraft ever designed and built, with hundreds remaining in use today, mainly as cargo planes. Even so, a fair share of DC-3s has met with unfortunate ends, including the one registered as NC16002.

That airliner had arrived at San Juan, Puerto Rico, at 7:40 p.m. Pilot Robert Linquist noted that the landing gear warning light was not working and that the batteries were low on charge. Linquist did not want to delay the return trip to Miami, Florida, and decided to use the plane's generator to charge the batteries mid-flight.

The plane took off at 10:03 with 32 passengers and crew, despite the drained batteries interfering with the plane's radio transmitter. Even so, the craft was able to complete routine radio transmissions until 4:13 in the morning, when it reported that it was about 50 miles south of Miami. It was never heard from afterward.

Oddly enough, despite being allegedly that close to Miami, Miami air traffic control did not receive the DC-3's last message. It was instead heard in New Orleans, about 600 miles away. Given that both cities had tried to warn the plane that the wind had shifted from northwest to northeast (although it is unknown whether the flight crew received that message), it is likely that the wind blew the aircraft off course. This would have been a big problem, given that the plane only had enough fuel for another hour and twenty minutes of flight time.

Even so, it seems strange that the plane should have vanished so thoroughly even with the Gulf Stream dispersing debris, given that the area where it disappeared contains relatively shallow water. In his 2007 book The Bermuda Triangle, David West reported a story about a diver named Dr. Greg Little, who claims to have discovered a DC-3 wreck about seven miles south of Bimini in the Bahamas that may be consistent with NC16002's description. However, DC-3s were also widely employed in the drug trade in the Bahamas during the 70s, so that's something to keep in mind.

7. SS Marine Sulpher Queen (February 4, 1963)

The Sulpher Queen was among the 533 T2 oil tankers built during World War II to help transport vital oil to the war effort. Originally christened as the SS Esso New Haven in 1944, she was renamed and converted in 1960 to transport molten sulfur in a single tank that spanned 306 feet of its total 524-foot length.

Her final voyage began three years later when she set out from Beaumont, Texas, on February 2nd, for Norfolk, Virginia. She carried 15,000 tons of molten sulfur, kept at 275 degrees, along with 39 crew members. Her last known position was a point approximately 350 miles west of Dry Tortugas, according to her final radio message on the 4th. When communications failed over the next two days, a nineteen-day search was called, mainly focusing on the Straits of Florida. While some debris, including life preservers bearing the ship's name, was located, neither the ship itself nor her crew members have ever been discovered.

Let's get a few facts straight before we go from zero to aliens here. The T2 tanker class was infamous for being remarkably prone to catastrophic structural failures. They were particularly prone to breaking in two in rough or cold seas, primarily due to their speedy construction, which entailed welding the steel hull plates together instead of attaching them with rivets. Indeed, such structural weaknesses were observed on the Marine Sulpher Queen before she set out on her fateful voyage (one of her crew members even told his wife that the ship was a "floating garbage can"). But her owners, greedy capitalists that they were, insisted that the vessel set out anyway so they wouldn't lose profits. Given that sixteen-foot waves were reported in the area around the time of the disappearance, it's entirely possible that the ship broke in two and rapidly sank like all the other T2 tankers before her.

There is also the possibility that the ship's highly flammable sulfur cargo may have ignited and blown the ship to pieces. The Sulpher Queen's tank was remarkably leaky, and fires often started around it. The leaking sulfur would puddle and cake around vital electrical equipment, causing it to short out. While I haven't found any sources other than the 2005 book Ghost Ships by Angus Konstam to back this up, there have also been reports that a ship out of Honduras reported sailing through a patch of ocean that smelled strongly of sulfur off the west tip of Cuba around four days after the Sulpher Queen vanished.

A much more interesting development occurred in January 2001. According to an article on texasescapes.com, a group of scuba divers claimed to have found a capsized wreck in the Gulf of Mexico about 140 miles west of Fort Meyers, Florida, that fit the Marine Sulpher Queen's description in 423 feet of water. Sadly, there does not seem to have been any new developments regarding that wreck since then.

8. The Witchcraft (December 22, 1967)

This mystery revolves around a 23-foot cabin cruiser owned by hotelier Dan Burack. He had invited a close friend, Father Patrick Horgan, on an evening cruise to see the Miami Christmas lights from offshore. They planned to cut the engine near buoy #7, about a mile offshore, and take in the scenery.

The trouble started around 9 p.m. when Burack radioed the Coast Guard to inform them that the cruiser's propeller had struck a submerged object and the boat needed to be towed back to shore. Burack seemed calm, perhaps because a) he had recently had the Witchcraft's hull fitted for a flotation device that rendered the cruiser virtually unsinkable, and b) he had flares with which he could signal passing boats should the need arise.

This makes it seem all the more baffling that when a Coast Guard vessel did reach buoy #7 just 19 minutes later, there was no sign of the Witchcraft whatsoever. Not even a subsequent six-day long 24,500 square mile search could turn up any evidence of the missing vessel.

So what happened? Here are some theories:

-A thunderstorm that passed through the area that night swept the cruiser away. The problem is that Burack could have easily radioed another SOS in that case.

-Another possibility is that the fast-moving Gulf Stream current carried the Witchcraft away from buoy #7 without Burack or Horgan noticing. This seems somewhat unlikely, however, not only because of the flotation device but also because, again, nothing was stopping Burack from sending out another distress signal.

-By far the most intriguing theory (at least for those who don't buy into more supernatural explanations), as proposed by the likes of blogger Michelle Merritt and the YouTube channel Bedtime Stories, is that Burack and Horgan faked their apparent deaths to avoid culpability for a criminal past.

Merritt notes that, at least to one familiar with the geography of the Miami waterfront, Burack's route makes no sense. The biggest reason is that Burack and Horgan sailed into the Atlantic to view the Christmas lights, which should have been easier to see from within Biscayne Bay. She also notes that buoy #7 is not a mile offshore, as most reports claim, but only 300 yards from South Pointe Park, which marks the entrance into Government Cut. Furthermore, Burack's home was about 2.5 miles north of South Pointe Park, so he was going rather far for such a casual outing. All of this led Merritt to conclude that Burack and Horgan lied about their actual position to the Coast Guard, presumably to lead them on a wild goose chase.

But why? Merritt notes that Miami was in dire financial straits at the time. Several millionaires living in the city had been robbed, with the thieves using the waterfront as a highway to untold riches. Burack had been struggling financially for years, especially after his Galen Hall Hotel burned down under curious circumstances in 1963. After completing a new resort, the Galen Beach, he sold out his interest in the property. With the city going down the tubes, Burack likely saw that his hotelier career was over, and he and Father Horgan sailed off into history.

Also worth noting is what happened to one of Burack's neighbors precisely one month after the Witchcraft disappeared. On January 22nd, 1968, Saverio "Sam" Codomo, a real estate developer with Mafia ties, was throwing a party for his recently wed daughter when two masked bandits broke in and tied everyone up. They stole several valuable coins and escaped by boat.

Coincidence? Who knows?

9. SS Sylvia M. Ossa (October 15, 1976)

This T2 tanker was christened Egg Harbor in 1943, was rebuilt as a bulk carrier in 1963, and had been renamed seven times throughout her years of service. She set out from Rio de Janeiro with a cargo of iron ore bound for Philadelphia and was reported lost alongside all 37 crew members around 140 miles west of Bermuda. If the New York Times is to be believed, the only debris ever recovered was an oil slick, a capsized lifeboat, and a life preserver with scorch marks.

Many Triangle enthusiasts are quick to jump on supernatural explanations due to statements from a Coast Guard spokesman that the weather was clear that day, with calm seas and visibility for forty miles. However, the same New York Times article mentioned above also notes that two days before the Ossa was reported missing, she had set out a radio message stating that she had run into gale-force winds and thus would be overdue for her arrival in Philly. The seas may have been much heavier than the crew anticipated, however.

10. SS Poet (October 1980)

This ship started as the USS General Omar Bundy in August of 1944, serving as a transport ship for the US Navy in the final months of World War II. She remained in military service until 1964 when she entered the private sector and was converted into a cargo ship. She changed names several times and was going by the SS Poet when she sailed on her final voyage.

She departed Philadelphia on October 24th, 1980, carrying 34 crew members and 13,500 tons of yellow corn bound for Port Said, Egypt. The ship radioed its position off Cape Henlopen, Delaware, at 9:00 that evening. When it failed to radio any updates by November 3rd, six days before its scheduled arrival at Port Said, a massive search covering over 750,000 square miles was called. Not a single piece of debris was recovered.

Theories for what happened have included that the ship was hijacked by Iranian terrorists, pirates, or the New Jersey-based Gambino crime family. Another theory is that a storm that rolled across the ship’s route the night after its departure from Philly sank it. Some have even suggested that water might have gotten into the cargo hold and caused the corn to expand to the point that it could have ruptured the hull. While the ship was old and likely had been kept in service long after it should have been retired, it seems rather unlikely that the hull was that flimsy. Then again, as one “Dr. Hess” commented on the WordPress version of this article: “The Poet was said to be a total POS rustbucket. I sailed with people that lost close friends on it.”

Others have suggested that a rogue wave might have capsized the ship. These unpredictable waves, reaching 80-100 foot heights, have been known to spring up during storms to swallow ships whole. Indeed, a possible rogue wave has also been implicated in the disappearance of the Sylvia M. Ossa.

Hopefully, by now, one can see that the Bermuda Triangle mystery really isn't a mystery at all. Practically every significant reported disappearance reported in the region has a logical explanation when you really look into it. To be fair to the fringe theorists, the Triangle region has played host to several UFO reports and even some sea monster sightings. One particularly unusual case involves the crew of the famous submersible Alvin, who allegedly encountered a creature that looked awfully similar to a small plesiosaur in October of 1969 while inspecting undersea cables in the Tongue of the Ocean in the Bahamas. Then again, I learned about that particular incident from another Charles Berlitz book, Without a Trace, so maybe take that one with a grain of salt.

Even so, as I stated at the top of this article, practically every source knowledgeable about the area, from the Coast Guard to NOAA to Lloyd's of London, has denied that the Bermuda Triangle is any more dangerous than any other part of the ocean, especially considering the heavy air and sea traffic that goes through the region every day. Indeed, when the World Wide Fund for Nature published a study demonstrating the ten most dangerous waters for shipping in 2013, the South China Sea, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean made the cut, but not the Bermuda Triangle. Indeed, the Bridgewater Triangle seems to offer the average mystery hunter more than the Bermuda Triangle.

And that's all I have to say about the Bermuda Triangle, but not the rest of the Vile Vortices. Tune in next time for the conclusion of my paranormal triangles world tour, where I examine Ivan T. Sanderson's theory to see if there is anything to his theory of there being twelve Bermuda Triangles! See you soon!